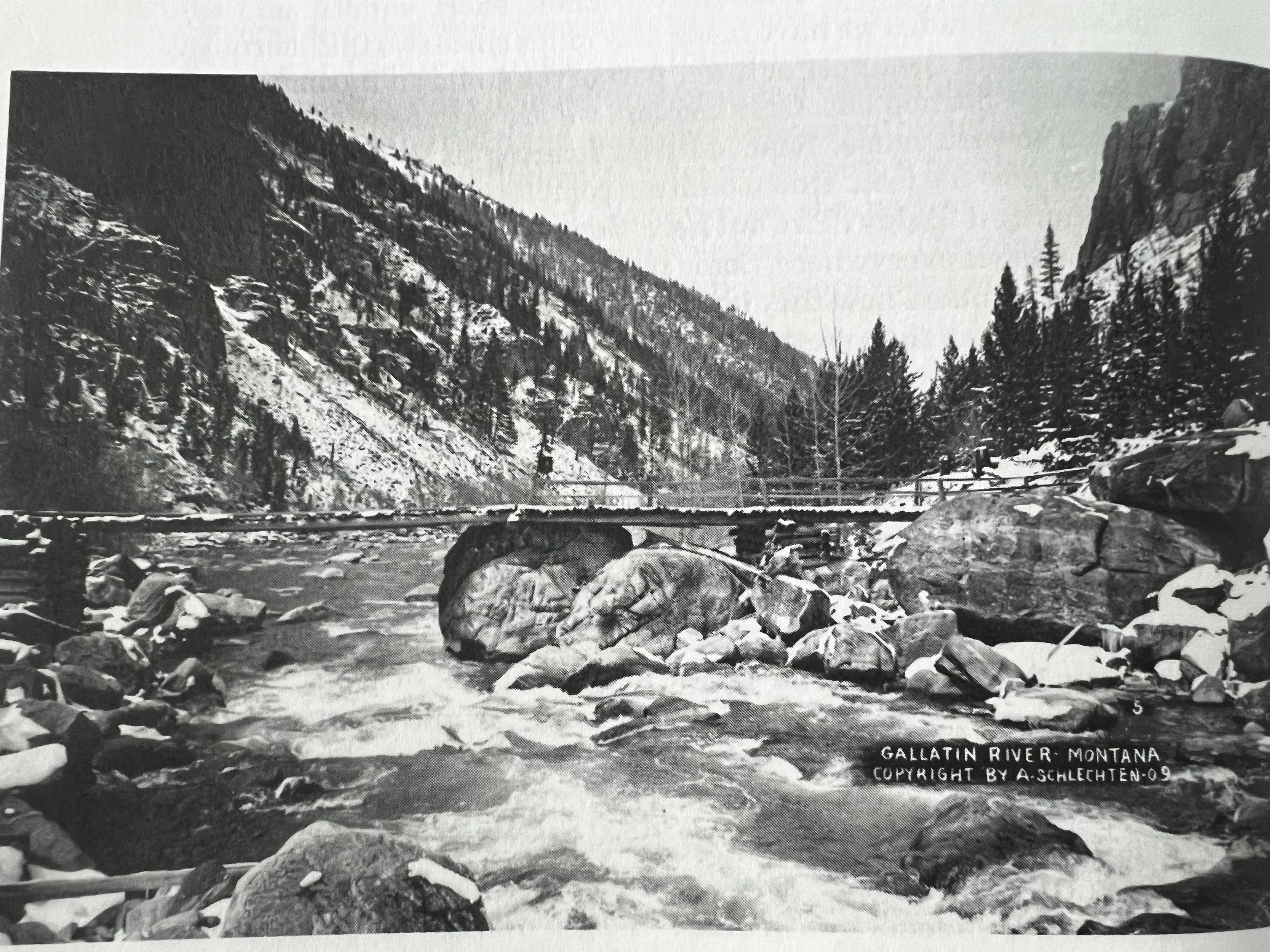

The Gallatin Road: How Pioneers Blazed Through the Canyon

House Rock. Museum of the Rockies Photo Archives, Photo taken from Montana’s Gallatin Canyon

Picture it—Gallatin Canyon in the 1800s. A place where rugged, raw beauty crashes against the brutal reality of untamed wilderness. For a paddleboarder who now sees the Gallatin River as the perfect stretch of whitewater, it’s hard to imagine this canyon as an obstacle—an unforgiving beast that ranchers, trappers, and prospectors had to wrestle into submission. But that's exactly what it was. No smooth paths, no easy put-ins, just jagged cliffs, dense forests, and a river that refused to be anything but wild.

Before Gallatin County was even a thing, before anyone thought about turning the high plains into pastures, the canyon was already calling. Not to adventure-seekers with paddleboards strapped to their roofs but to homesteaders and cattlemen looking for ways to move their herds through the land. Nels Murray, one of those early rugged types, blazed the first pack trails through here, pushing further into the wild where only game trails and Indian paths dared to tread.

And that's where the story of the Gallatin Road begins—a road that would transform this canyon from a desolate obstacle into a crucial passageway. It wasn’t just a path through the woods; this was a lifeline for the ranchers and prospectors whose livelihoods depended on being able to get cattle to summer pastures and supplies to isolated mining camps.

But this was no cakewalk. Early attempts to tame the canyon were full of fords, bluffs, and sketchy river crossings. The trail from Bozeman met the Gallatin at Spanish Creek, navigating treacherous terrain with the narrowness and unpredictability of a Class V river run. They’d ford Spanish Creek, then the Gallatin, cross Sheep Rock, Castle Rock, Squaw Creek, and finally, when the earth gave them no other option, they’d scrape by on whatever game trail they could find. Imagine that on horseback—no Gore-Tex, no waterproof boots, no quick-dry anything. Just sweat and dirt.

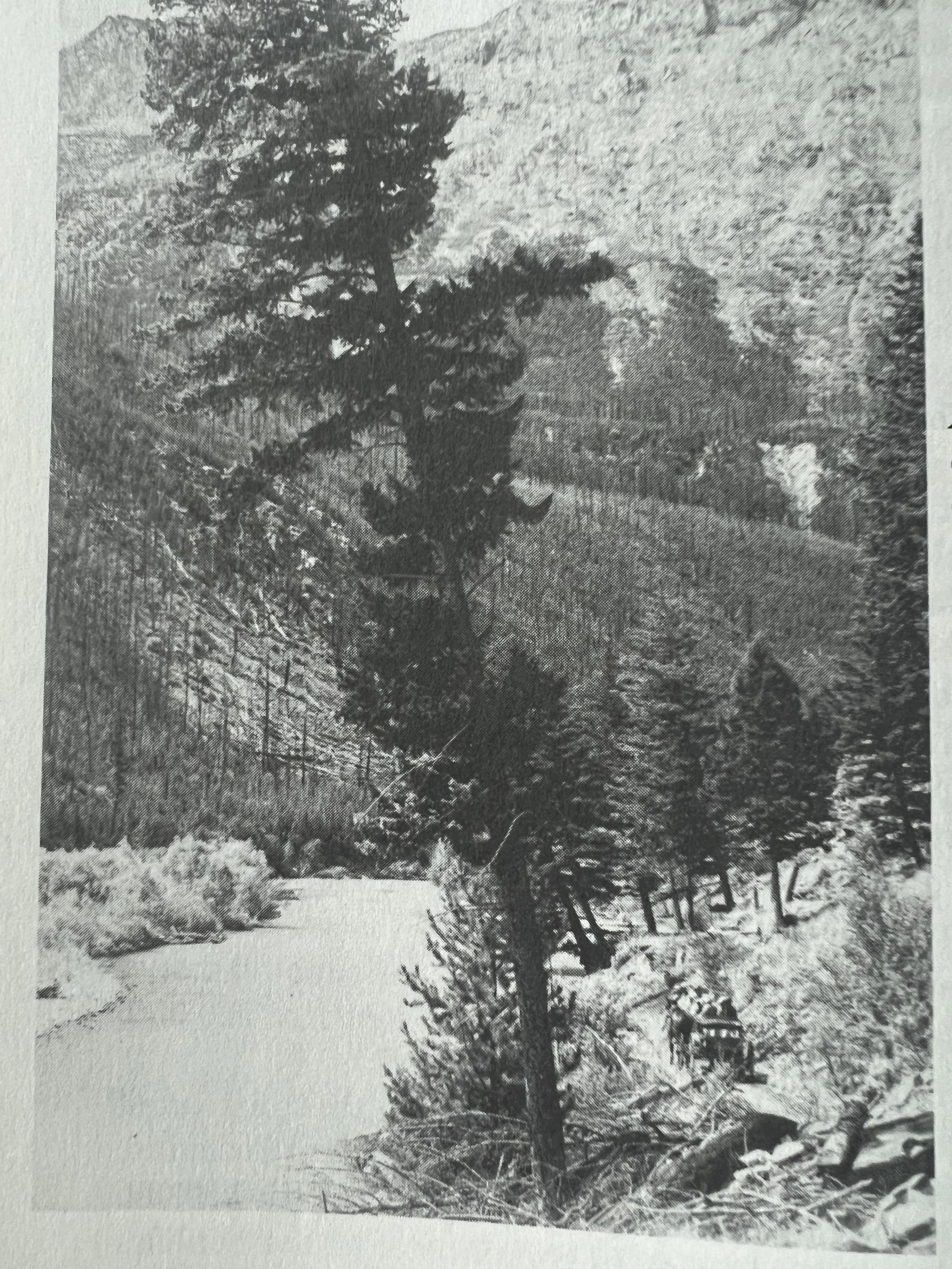

Museum of the Rockies Photo Archives, Photo taken from Montana’s Gallatin Canyon

By the 1880s, Gallatin Valley was hungry for a real road. Ranchers needed to get their cattle through, and more than that, there were dreams of connecting Bozeman to Yellowstone. The idea wasn’t just to survive but to thrive, to build a road that opened the basin to trade, tourism, and profit. The Gallatin Canyon became an irresistible prize, and so the battle began between the canyon and the people who thought they could conquer it.

But you don’t tell the Gallatin what to do.

The first serious plan came from W.W. Wylie, a guy who knew the importance of making this canyon passable. He was a tourist operator, shuttling people into Yellowstone, and grazed thousands of horses at Spanish Creek. His clients needed easy access, and he was ready to bulldoze through. The idea caught fire, and the Gallatin County Commissioners sent out engineers to plot the course.

From the very start, it was a mess. The steep bluffs, endless switchbacks, and unpredictable weather made road-building a saga of failed attempts and wasted resources. In 1892, after almost two decades of lobbying, Lewis Michener (you could say the Gallatin Canyon’s original diehard) gathered six hundred signatures from the region’s toughest men. This was before there was such a thing as an easy vote—those signatures were like a collection of scars earned on the canyon's brutal frontlines.

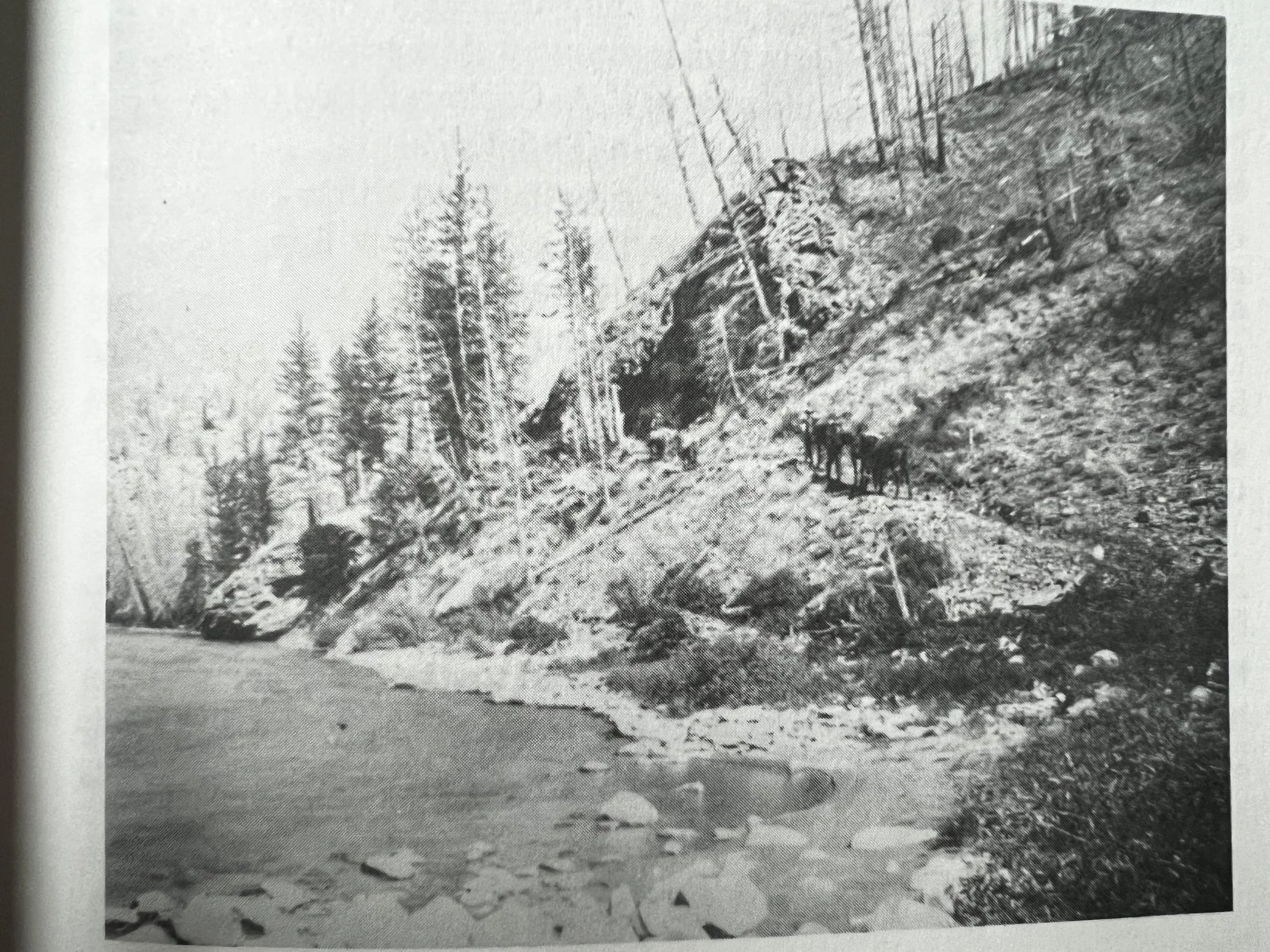

Michener’s Bridge - Museum of the Rockies Photo Archives

Michener wasn’t just fighting for himself. Ranchers, loggers, and everyone who wanted a piece of the Gallatin’s riches lined up behind him. They weren’t talking about paddling down this river for fun; they were desperate to survive by harnessing every piece of this canyon they could. And in 1897, after years of grinding, the county finally caved. Contracts were awarded, bridges were promised, and Cockerell (the contractor who knew more about bridging gaps than most politicians) started work.

July 1898. The first wagon rumbles down the newly hacked-out road. It wasn’t pretty—far from it. Cockerell’s “road” was full of bumps, ten feet wide at best, and often impassable in the winter. But it was enough to light a fire under the region’s development. The West Fork and Taylor Fork were now open for business, and the canyon wasn’t a mystery anymore. Men like Tom Michener were the first to take their wagons up the route, building bridges and clearing paths as they went. His sister, Mamie Michener, even joined the charge, riding beside him in a wide skirt, breaking down every gender boundary alongside the trees and cliffs they demolished.

And that's how it went—the road kept growing, and with it, the Gallatin Canyon was carved, cut, and shaped into a livable space. Cattle herders moved their beasts into the upper basin, and the Gallatin Basin was no longer the canyon's dark secret—it was a place people could reach.

By the 1900s, with the road snaking all the way to Taylor Fork, the canyon’s battle was mostly won. But there was still the dream of connecting it all the way to Yellowstone. That’s when Sam Wilson stepped up with a bold bet: the road should go to Mammoth through the Big Horn Pass. It was a reckless wager, the kind of thing river guides would dare each other to do on a calm float—but this was no float. It was all or nothing.

Portal Creek - Museum of the Rockies Photo Archives, Photo taken from Montana’s Gallatin Canyon

Spoiler alert: Wilson lost the bet. The road didn’t go to Mammoth. Instead, it wound down to West Yellowstone, and the fight to tame the canyon evolved from survival into something more—progress. By 1910, the government finally stepped in, recognizing that this wasn’t just about people moving cattle or supplies. The automobile was coming, and Gallatin County was going to need a road that could handle the next wave of adventurers, homesteaders, and opportunists.

As a paddleboarder, you carve your own path on the Gallatin today, but those early pioneers? They hacked their way through a canyon that did everything it could to break them. Their struggle wasn’t about finding the fastest line down a rapid—it was about surviving the relentless grind of the canyon. Every log laid down to make a road, every ford that became a bridge, and every boulder they moved to make this place accessible, is part of the river you now know.

So the next time you drop into the Gallatin, remember: this isn’t just water under your board. It’s the blood, sweat, and grit of people who saw the canyon as something to be tamed, even when it fought back with everything it had. They didn’t conquer it. They carved out a piece of it, just enough for you to float through today.

Taylor Creek Falls Museum of the Rockies Photo Archives