The Coming of the Railroad: Transforming Gallatin Canyon

The late 19th century saw significant transformations in the American West, particularly with the advent of railroads. Gallatin Canyon, located in Montana, was no exception. As the Northern Pacific Railroad expanded westward, reaching the Gallatin area in the 1880s, its presence marked a pivotal point in the region's development. The demand for timber, mining resources, and transportation of goods to burgeoning towns fueled this railroad expansion, forever altering the landscape and the pace of life in this once-remote region.

Railroad Expansion and Land Grants

The railroad’s expansion was incentivized by the U.S. Congress through a series of land grants. When the Northern Pacific Railroad was chartered in 1864, the government awarded the company every other section of land—640 acres per section—along a twenty-mile-wide belt on each side of the track. In Montana’s undeveloped territories, the railroad claimed every second section of land forty miles out from the tracks. As a result, the railroad’s influence over the land was profound, extending far beyond the steel rails.

Sections of this granted land were sold, often in lieu of monetary payments, with particular value placed on lands that produced valuable timber and agricultural products. By the 1880s, these economic drivers pushed the railroad’s interest deep into the Gallatin Canyon. Lumber from the canyon’s timber-rich forests would soon supply the burgeoning mining and construction needs of Montana’s rapidly growing towns, particularly Bozeman and those in Alder Gulch, where gold and other precious metals were extracted.

The Logging Camps and Early Settlers

One of the key figures in the Gallatin Canyon’s transformation was Zachary Sales, who operated a sawmill at Salesville (now Gallatin Gateway) and supplied timber for the Northern Pacific Railroad's expansion. As early as the 1880s, Sales and his workers were cutting timber as far south as the Taylor Fork drainage. The loggers constructed rudimentary dams in side creeks and sledded logs through the waterways, harnessing the power of the river to transport the lumber downstream.

The work was grueling and often dangerous. Creeks were dammed in the winter, and come spring, the timber was rolled into the rushing streams. The logs were floated down the Gallatin River, creating treacherous logjams. An account from the Avant Courier recounts a harrowing adventure in May 1883, where a man attempted to free a massive jam of timber lodged in the canyon. Facing the boiling waters of the Gallatin, filled with sharp rocks and unpredictable currents, this man’s survival seemed impossible. Yet, after a grueling battle with the river’s obstacles, including narrowly escaping after his lifeline shrub gave way, he managed to free the jam. His bravery earned him recognition, though he himself remained humble, merely recounting the harrowing experience.

Albert Greek: Sawmill Operator and Pioneer

One of the most fascinating characters to emerge from this time was Albert Greek, a Scottish immigrant who established a sawmill in Salesville and became an important player in the canyon’s timber industry. Greek, a towering figure with a thick beard, had an intriguing backstory. He had supposedly abandoned a career in medicine in Scotland due to an unrequited love. In the Gallatin Canyon, he found a new purpose, running his sawmill at the creek that still bears his name—Greek Creek.

Greek's sawmill was crucial in providing lumber for the railroad's expansion, and he played a significant role in trail construction between Middle Creek and Squaw Creek, which enabled supplies to reach his camp more easily. Eventually, Greek sold his sawmill to Lewis Cass Bartholomew for $375 and mysteriously disappeared from the Gallatin Canyon’s records.

The Role of Bozeman’s Businessmen

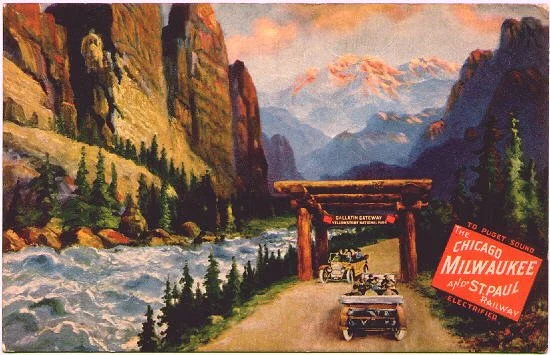

As the railroad advanced, Bozeman’s businessmen saw an opportunity. In 1872, when President Ulysses S. Grant created Yellowstone National Park, it became apparent that tourism and industry could intersect. Bozeman’s entrepreneurs wanted to establish their town as a key gateway to the park. The initial vision was for tourists to travel through Gallatin Canyon by stagecoach, en route to Mammoth Hot Springs via Gardiner Hole. The railroad would not only bring tourists to the park but would also supply the logging camps in the canyon and tap into the wealth of minerals, coal, and timber in the region.

Two Bozeman businessmen, Walter Cooper and George Wakefield, along with civil engineer Peter Koch, spearheaded an exploratory trip into the Gallatin Canyon in August 1881 to assess its potential for railroad ties and mineral deposits. Koch meticulously documented the trip, describing the rugged terrain, the abundance of timber, and the plausibility of establishing a rail line through the canyon. However, after several setbacks, including a devastating fire and the realization of the high cost of construction, the Northern Pacific Railroad ultimately chose a different route through the more easily accessible Yellowstone Valley.

The Devastating Fires of 1881

In addition to the economic challenges faced by those hoping to establish a railroad spur through the canyon, natural disasters wreaked havoc. In the fall of 1881, a massive wildfire ravaged the Gallatin Canyon, further complicating any plans to develop a direct rail line through the area. Walter Cooper’s journal details the harrowing experience of traveling through a landscape devastated by the fire, describing the thick clouds of smoke, the charred remains of trees, and the eerie red glow that illuminated the night sky.

The fire destroyed huge swathes of timber—timber that was sorely needed for the railroad ties. Though the blaze was eventually extinguished, it left a scar on the landscape, reducing the profitability of the logging industry and diminishing the canyon’s viability for railroad expansion.

Survival Through the Flames

One of the most gripping accounts comes from Walter Cooper’s harrowing journey during the fires of August 1881. His journal entry from August 28 describes a desperate race against the advancing flames. After waking at dawn to continue his trek, Cooper faced the creeping fire from all sides. As the inferno intensified, he and his party had no choice but to travel through hot ashes and burned-out sections of the forest. With little feed left for their horses and their supplies running low, they pushed forward in near-blind conditions, enduring the stench of smoke and the deafening noise of the fire around them.

Cooper’s account highlights the rugged endurance required to survive such challenges. His horses, their hooves sore from the scorching ground, struggled to carry the party and their supplies, while thick smoke made breathing and navigation nearly impossible. By the evening of August 30, Cooper’s group had covered over fifty miles since morning, eventually making camp near Hell Roaring Creek, exhausted but alive. By the time they reached home on August 31, they had narrowly escaped the worst fire the canyon had seen in decades.

The Legacy of the Gallatin Canyon Railroad Plans

Despite the setbacks, including the fires and the high cost of construction, Bozeman’s businessmen didn’t entirely abandon their dreams of connecting their city to Yellowstone National Park. While the railroad spur through Gallatin Canyon never came to fruition, the exploratory efforts by Cooper, Wakefield, and Koch paved the way for future development in the region. The timber industry continued to thrive in the canyon for years, and the Gallatin River itself became a lifeline for transporting materials through the otherwise impassable terrain.

The legacy of this period in Gallatin Canyon’s history is visible today. The place names, from Salesville to Greek Creek, and even Robber’s Roost—a log cabin built by Sam Harper of Bozeman for lumberjacks—still evoke the rugged spirit of the canyon’s early settlers and the challenges they faced.

Conclusion

The story of the railroad's arrival in Gallatin Canyon is a tale of ambition, industry, and resilience. From the daring exploits of loggers navigating treacherous waters to the entrepreneurs hoping to establish a vital transportation link to Yellowstone National Park, the railroad era in the canyon was marked by significant challenges. Fires, logjams, and economic realities ultimately altered the trajectory of the railroad’s expansion, but the impact on Gallatin Canyon’s development was profound. The canyon, once a remote wilderness, became a hub of industrial activity, leaving a legacy that still echoes in the landscape today.

Source: "Montana's Gallatin Canyon: A Gem in the Treasure State" by Janet Cronin and Dorothy Vick.