The Gold Rush in Gallatin Canyon: A Detailed Exploration

Gold, with its unmistakable allure, has drawn countless people into some of the most rugged and remote areas of the American West. The story of gold mining in Gallatin Canyon, located in southwestern Montana, is no exception. From the early days of the California Gold Rush, when prospectors fanned out into the Rocky Mountains in search of new wealth, to the tales of failed expeditions and lost sluice boxes, the history of Gallatin Canyon is steeped in adventure, hardship, and the hope of striking it rich.

This blog entry, drawn from Montana’s Gallatin Canyon: A Gem in the Treasure State by Janet Cronin and Dorothy Vick, delves into the rich history of gold mining in Gallatin Canyon, a place where prospectors dreamed big but more often than not came away empty-handed.

The Gold Fever Spreads to Montana

In 1848, the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in California set off a wave of gold fever that rippled across the western United States. As prospectors spread out from California, they began to search every promising nook and cranny of the Rocky Mountains. By 1862, gold was discovered in the Beaverhead Valley of Montana, leading to the establishment of Bannack, the first major gold-mining town in Montana. The flood of people seeking their fortunes didn’t stop there. Prospectors soon turned their eyes toward Gallatin Canyon, hoping that its creeks and streams would hold the next big lode.

Early Placer Mining Methods

In the early days of prospecting, miners used a simple method known as placer mining to search for gold. Placer deposits, made up of glacial and alluvial sands and gravels, were the result of the erosion of mineral-rich rocks high in the mountains. Snowmelt, rain, and ice wore down gold-bearing rock, carrying small particles of gold downstream, where they would settle in riverbeds and gulches. As heavier than most other materials, gold would sink to the bedrock while the lighter sand and gravel would wash away.

To extract this gold, prospectors used rudimentary tools: a pick, a shovel, and a gold pan. They collected sand and gravel from just above the bedrock, combined it with water, and swirled it in the pan. The lighter material would wash away, leaving behind the heavy gold. Black sand—composed of iron and other heavy minerals—was often found alongside the gold, and its presence was a good indicator that gold might be nearby. Many hopeful miners found themselves panning the creeks of Gallatin Canyon, hoping to find a fortune.

The Challenge of Inexperience

Despite the apparent simplicity of placer mining, many early prospectors lacked the knowledge and skills needed to succeed. As recounted in Montana’s Gallatin Canyon, many of these early fortune seekers were not experienced miners. Some even used their frying pans to search for gold, only to discover that grease left on the pan would cause the gold to float away with the water. Tom Michener, a seasoned prospector in the area, advised others to burn their pans in a campfire to remove any grease residue and warned against putting their hands in the gold pans. Michener spent many years searching the Gallatin Canyon for gold, sharing his hard-earned knowledge with newcomers.

Despite these challenges, the allure of gold kept prospectors coming. Many spent years searching without success, living off the hope that their next pan of gravel would yield the strike that could change their fortunes. Some succeeded in convincing others to “grubstake” them—providing supplies in exchange for a share of any gold found. However, more often than not, these prospectors were left with little more than stories of dreams deferred.

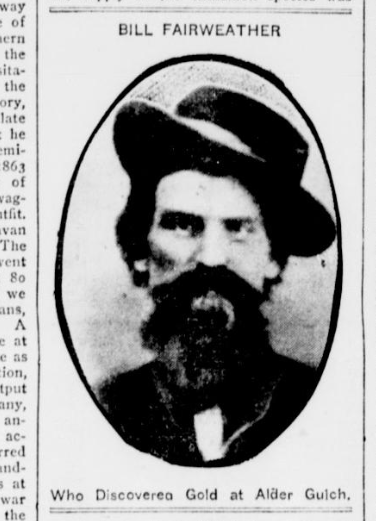

Bill Fairweather and the Gallatin Gold Rush

One of the most famous prospectors to pass through Gallatin Canyon was Bill Fairweather, who had played a key role in the discovery of gold at Alder Gulch, one of the richest strikes in Montana. In the winter of 1863-64, Fairweather led a group of miners from Virginia City into the Gallatin Canyon, telling them of rich deposits he had supposedly panned near Black Butte Creek. The men followed Fairweather through deep snow and freezing temperatures, but their journey soon became a tale of hardship.

As they crossed the Madison Divide, a severe snowstorm caught the group. Instead of turning back, they pressed on, hoping to reach the gold that Fairweather had spoken of. However, conditions worsened, and nearly all their horses starved to death. The men, already low on supplies, realized that the gold Fairweather promised was nowhere to be found. Eventually, they abandoned their efforts, crossing the Gallatin Mountains and making their way down to the Yellowstone Valley, cursing Fairweather as a “damned liar.”

Despite their failure, the expedition remained a legend. Fairweather’s tales of gold in Gallatin Canyon continued to draw prospectors, many of whom left empty-handed.

The Lost Sluice Box: A Legend of Gallatin Canyon

Perhaps the most famous story of Gallatin Canyon’s gold-mining history is that of the “lost sluice box.” In 1864, an old man and his son arrived in Gallatin Canyon from Nebraska, determined to prospect for gold. By the time winter set in, they had dug approximately $1,000 worth of gold out of the canyon’s upper reaches. As they prepared to return home, their horses starved, and the father passed away, leaving the young man to fend for himself.

After his father’s death, the son packed up their gold, secured a sack of marten skins, and returned home to Nebraska, where he organized a new expedition to retrieve the rest of their gold. However, the young man became confused upon returning to Gallatin Canyon and was unable to locate the original site of their diggings. Thus began the legend of the lost sluice box, a treasure trove of gold that was said to be hidden somewhere in the upper reaches of the canyon.

Many prospectors would later search for the lost sluice box, but none ever found it. The mystery of the lost gold added to the lore of Gallatin Canyon, drawing even more hopeful fortune seekers.

Tom Michener and the First Cabin in Gallatin Canyon

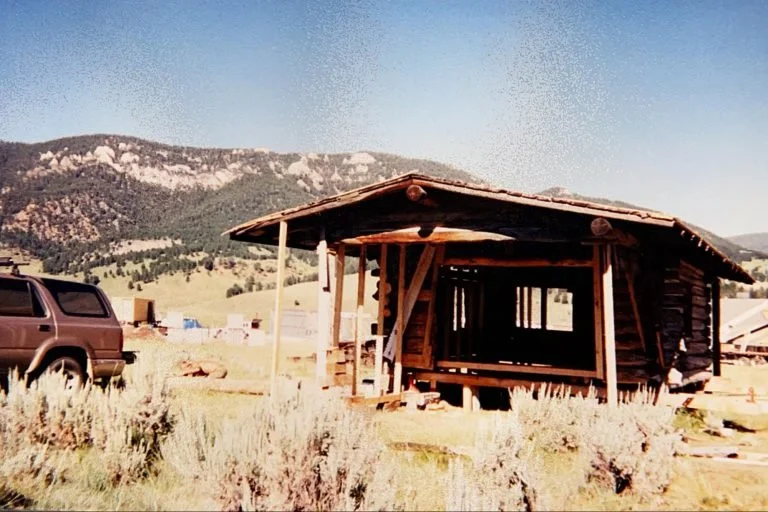

Tom Michener, who had warned prospectors to treat their gold pans with care, became a permanent fixture in Gallatin Canyon. In 1875, he and a partner built the first cabin in the canyon on the north side of the West Fork of the Gallatin River. As described in Montana’s Gallatin Canyon, the cabin was only a shell by 1917, but it stood as a testament to the early days of prospecting in the area.

Michener’s diary recounts his years of prospecting in Gallatin Canyon, during which he combed every creek and stream in search of gold. He even scouted for gold on the Snake River and later worked as a surveyor for the government. Despite his years of effort, Michener never found significant gold in the canyon, but his stories and experiences made him a legend in his own right.

The Shift from Mining to Ranching

By the 1880s, the rush for gold in Gallatin Canyon had begun to fade. The population of miners dwindled as they either moved on to other goldfields or shifted their focus to agriculture. Ranching and cattle grazing became more prominent, and the Gallatin Valley transformed from a region of prospectors to one of farmers and ranchers. The fertile lands of the valley, paired with the rich grazing opportunities in Gallatin Canyon, made the area ideal for raising cattle and horses.

By 1880, the demand for grazing land in Gallatin Canyon had grown so strong that ranchers began driving their herds into the canyon’s Spanish Creek area and other nearby basins. The transition from gold mining to agriculture marked a turning point in the history of Gallatin Canyon, one that would shape its future for generations to come.

Conclusion: Gallatin Canyon’s Legacy

The story of gold mining in Gallatin Canyon is one of adventure, persistence, and ultimately, adaptation. While the prospectors who panned the canyon’s creeks in search of fortune often came away empty-handed, their efforts left a lasting impact on the region. The tales of the lost sluice box and the hardships of the Fairweather expedition continue to capture the imagination, while the transition to ranching laid the foundation for the Gallatin Valley’s future prosperity.

Though the days of gold panning in Gallatin Canyon are long past, the canyon remains a place of natural beauty and historical significance. The legacy of those who searched for gold lives on in the stories they left behind, reminding us of the trials and tribulations of life in the Old West.

Source: "Montana's Gallatin Canyon: A Gem in the Treasure State" by Janet Cronin and Dorothy Vick.